– There are many gaps in the regional historiography in what concerns the study of the daily life of women, especially corporeality and sexuality. Speaking about these things was considered “improper” in the traditional culture, causing a deficit of available sources, – explains Yulia Litvin, who did research relying on the available body of historical, ethnographical, and linguistic sources, as well as material from her own field trips.

Yulia Litvin, Researcher at the Ethnology Section ILLH KarRC RAS. Photo by M. Dmitrieva / KarRC RAS Scientific Communication Service

The transition of a Karelian girl to maiden status had ritual and magical, visual and social dimensions. A maiden in periods had to follow certain instructions. She was prohibited to go to public places and limitations were imposed on her household activities. Female “uncleanliness” was supposed to affect the outcome of the work. At the same time, the belief in female “uncleanliness” during periods was combined with expansion of the woman’s ritual functions, including healing and love magic.

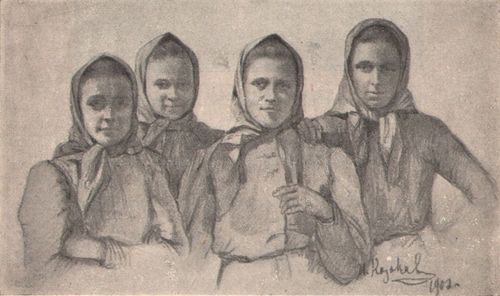

In order to secure her dignity and reputation while at the same time look appealing to the other sex a peasant girl had to keep balance between the prescribed morals and the activity needed to procure a husband. During holidays, a single peasant woman was allowed to interpret behavioral norms more freely.

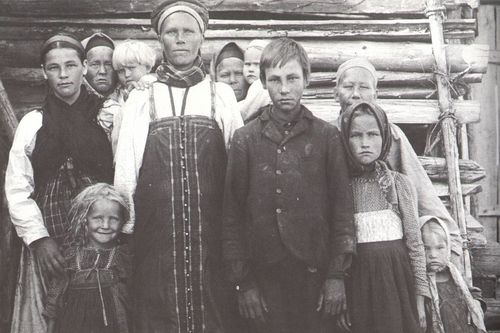

A Karelian family from Voknavolok Village. Photo by A.R. Niemi, 1904. Virtaranta P. Vienan kyliä kiertämässä. Helsinki, 1978

The next major stage in the life of a woman, which not only influenced her body but also entailed a change in the social status, was pregnancy. Women delivered covertly – in a bathhouse or a cattle shed. A midwife or mother-in-law (after 1945 – an obstetrician) were invited, if possible, especially for the woman’s first birth-giving. However, as women often had to leave home, especially during field work time, labor could start in the field, in a boat, or on the road. A woman in labor was supposed to be steadfast and persevering.

In pre-Soviet time, a woman was kept in isolation for some time after giving birth. The new mother's transitional status indicated her “uncleanliness”, being dangerous for others and at the same time vulnerable to supernatural forces. The mother could be not allowed to breast-feed for the first time. Instead, the baby was given a teat made of cloth and soaked in sweetened water or a nursing bottle with boiled or freshly drawn milk. The clothes and things used in the delivery process acquired a sacral meaning for the new-born and served his/her protection.

Woman churning cream into butter, Kamennoe Ozero Village, Uhta District, 1927–1928 (Russian Museum of Ethnography). The Finno-Ugrian world through photographs and documents. Scientific legacy of L.L. Kapitsa. St. Petersburg, 2017. PÑ. 60.

Giving birth to a baby, especially a boy, let a daughter-in-law in a multi-generation family occupy a stronger position in the house and get more rights. Growing out of reproductive age in the mistress of the house signified the start of power transfer from the mother-in-law to the daughter-in-law.

The key functions for elderly Karelian women were up-bringing and social norm-setting. They looked after children and perceived themselves as a special group that supervises the village community. Ceasing to perform household functions, an elderly woman gained new opportunities for self-actualization outside the family. She could act as a wise woman, midwife, or wailer. Access to these occupations was opened, namely, by the woman’s becoming “clean” – without periods or sexual encounters.

“Female corporeality functions in the traditional culture at the physical and the symbolic levels, which are manifested through visual markers, behavior and even posture. Corporeality is linked to the world of things and to the space. By addressing this topic, we uncover a dimension of life that used to be tabooed in the traditional culture as well as widen our understanding of a woman’s experience and visualize the process of physiological reality transformation into cultural traditions”, – the author of the article sums up.