Scientists in different countries have noted that global warming is pushing the southern boundary of the main permafrost farther north. It is therefore necessary to set up permafrost monitoring in different regions of the Arctic zone. The dynamics of the Kola Peninsula palsa mires is also an important marker of possible climate changes. It is currently predicted that Fennoscandian palsa bogs may thaw completely within 40-60 years.

Filling in the knowledge gap on the condition of palsa mires in the Kola Peninsula is the key task for the research project of Karelian scientists supported by Russian Science Foundation grant # 22-77-10055. Within this study, specialists in different fields have designed an integrated method for studying these natural objects. The results of testing the method were published in the international journal of Remote Sensing.

– We undertook to determine how the surface signs of palsa degradation, which appear in the landscape features and vegetation composition, correlate with the interior state of permafrost and peat hydrology, - explained Pavel Ryazantsev, Project Manager, Senior Researcher at the Department for Integrated Research KarRC RAS.

Participants of the project for palsa mire research: Yulia Tkachenko, Pavel Ryazantsev, Aleksey Kabonen, and Stanislav Kutenkov

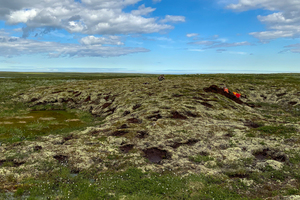

Fieldwork was carried out in a peatland in the Lovozero District of the Murmansk Region. Scientists photographed and measured sites using UAV-based aerial photography, described vegetation on the surface, "scanned" hummocks with GPR, manually drilled boreholes, and dug soil pits. Machine-learning methods were used to process the entire dataset and generate the final classification of the surface.

Based on the analysis of aerial photographs and on-the-ground botanical releves, the surface was divided into landscape classes. In turn, GPR images supplemented by boreholes provided an insight into the interior structure and hydrology of the peatland. These data were then aligned using machine-learning techniques. As a result, the researchers were able to determine how the state of the permafrost affects the distribution of landscape classes, and how the shape and size of the hummocks are related to the vegetation that covers them. Where permafrost is degrading, it shows up on the surface: mosses are replaced by herbaceous and dwarf-shrub communities, followed by trees.

The poor accessibility and wide distribution of palsa mires on the Kola Peninsula make the estimation of the full extent of their thawing challenging. So in the future, after machine learning based on the sample, the system will enable the state of the mires to be assessed using remote sensing data, without in situ surveys.

The research results from the Lovozero mire demonstrate that there is no doubt about the ongoing hummock degradation, whereas previously Russian scientists believed the condition of palsa mires on the Kola Peninsula to be fairly stable.

– This assumption was based on the annual thickness of the permafrost active layer. Recent studies, however, prove that active layer thickness is not a valid indicator, and that what really matters is the reduction of the hummock area. A distinctive feature of palsa mires is that their thawing is often spontaneous and very rapid. During the expedition to the Kola Peninsula eastern coast, we witnessed the collapse of a hummock literally in real time: its slope collapsed into a pond formed by meltwater. It's important to keep track of such processes, which is why continuous monitoring is necessary, - Pavel Ryazantsev explained.

Recording peat deposit stratigraphy – soil scientist Yulia Tkachenko at work

As another important result of the study, GPR data showed that the permafrost inside the hummocks does not always reproduce their shape. Scientists detected an asymmetric configuration of permafrost in some hummocks. They found it to be related to the accumulation of snow on the leeward slopes, and, as a consequence, to alteration of the freezing temperature. The authors thus confirmed that the degradation of palsa mires is influenced not only by the rising mean annual air temperature on the Kola Peninsula, but also by the amount of precipitation.

Permafrost thawing is not just a marker of climate change. It is usually accompanied by an increased release of greenhouse gases sequestered in frozen peat. This topic also needs to be studied further. In addition to developing a methodology for identifying and classifying palsa mires, Karelian scientists plan to create a system for automatic monitoring of the state of permafrost inside the palsa mires and their gas regime.

– For scientists, palsa mires are a natural laboratory or observatory, since the cycles of their growth and degradation are closely related to climatic factors. We can study the state of palsa mires and assess the transformation of permafrost and how these changes are connected to global climatic processes in the Northern Hemisphere, - the project manager summarized.

Photos by A. Kabonen / Petrozavodsk State University